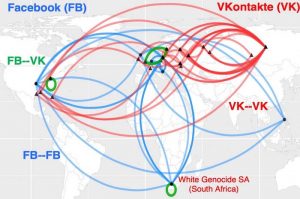

The paper was written after analysis using a “first of its kind” mapping technique, according to George Washington University, which worked with the University of Miami.

“We set out to get to the bottom of on-line hate by looking at why it is so resilient and how it can be better tackled,” said project lead Neil Johnson.

To understand how hate evolves on-line, the team mapped how clusters interconnect to spread their narratives and attract new recruits – clusters that form readily and easily, said GWU.

Focusing on Facebook and its central European counterpart VKontakte, the researchers started with a given hate cluster and looked outward to find a second one that was strongly connected to the original.

They discovered that hate crosses boundaries of:

- Internet platforms, including Instagram, Snapchat and WhatsApp

- Geographic locations, including the US, South Africa and parts of Europe

- Languages, including English and Russian

Clusters were seen creating new adaptation strategies in order to re-group on other platforms and, or, re-enter a platform after being banned.

“For example, clusters can migrate and reconstitute on other platforms or use different languages to avoid detection,” according to GWU. “This allows the cluster to quickly bring back thousands of supporters to a platform on which they have been banned and highlights the need for cross-platform cooperation to limit on-line hate groups.”

“This is why individual social media platforms like Facebook need new analysis such as ours to figure out new approaches to push them ahead of the curve,” said Johnson, whose team is building on its mapping and mathematical modelling to develop software that could help regulators and enforcement agencies implement interventions.

Given the right circumstances, four intervention strategies that social media platforms could use now, according to GWU, are:

- Reduce the power and number of large clusters by banning the smaller clusters that feed into them.

- Randomly ban a small fraction of individual users in order to make the global cluster network fall a part.

- Pit large clusters against each other by helping anti-hate clusters find and engage directly with hate clusters.

- Set up intermediary clusters that engage hate groups to help bring out the differences in ideologies between them and make them begin to question their stance.

The researchers noted each of their strategies can be adopted on a global scale and simultaneously across all platforms without having to share the sensitive information of individual users, or commercial secrets, which has been a stumbling block before.

The paper is ‘Hidden resilience and adaptive dynamics of the global online hate ecology‘ – only its abstract is freely available, which reveals this piece of information: “We observe the current hate network rapidly rewiring and self-repairing at the micro level when attacked, in a way that mimics the formation of covalent bonds in chemistry.”

Johnson is affiliated with the ‘GW institute for data, democracy, and politics’, which fights the rise of distorted and misleading information on-line, “working to educate national policymakers and journalists on strategies to grapple with the threat to democracy posed by digital propaganda and deception”, said GWU.

This research was supported by a grant from the U.S. Air Force.

Electronics Weekly Electronics Design & Components Tech News

Electronics Weekly Electronics Design & Components Tech News